Seeking Immorality: Ancient Artifacts

In every culture around the world, internment, or burial, is an important component of the life cycle. In Asia, the deceased were interred in tombs that reflected their status and with objects intended to serve and protect them in the afterlife. Featuring works from China, Japan, and Korea, Seeking Immortality offers insight into the nuances and complexities of ancient societies.

IMAGE CREDIT

Unknown, Pair of painted equestrian funerary figures, Han dynasty, 206 B.C.-220 A.D. Painted clay. Gift of Drs. Thomas and Martha Carter.

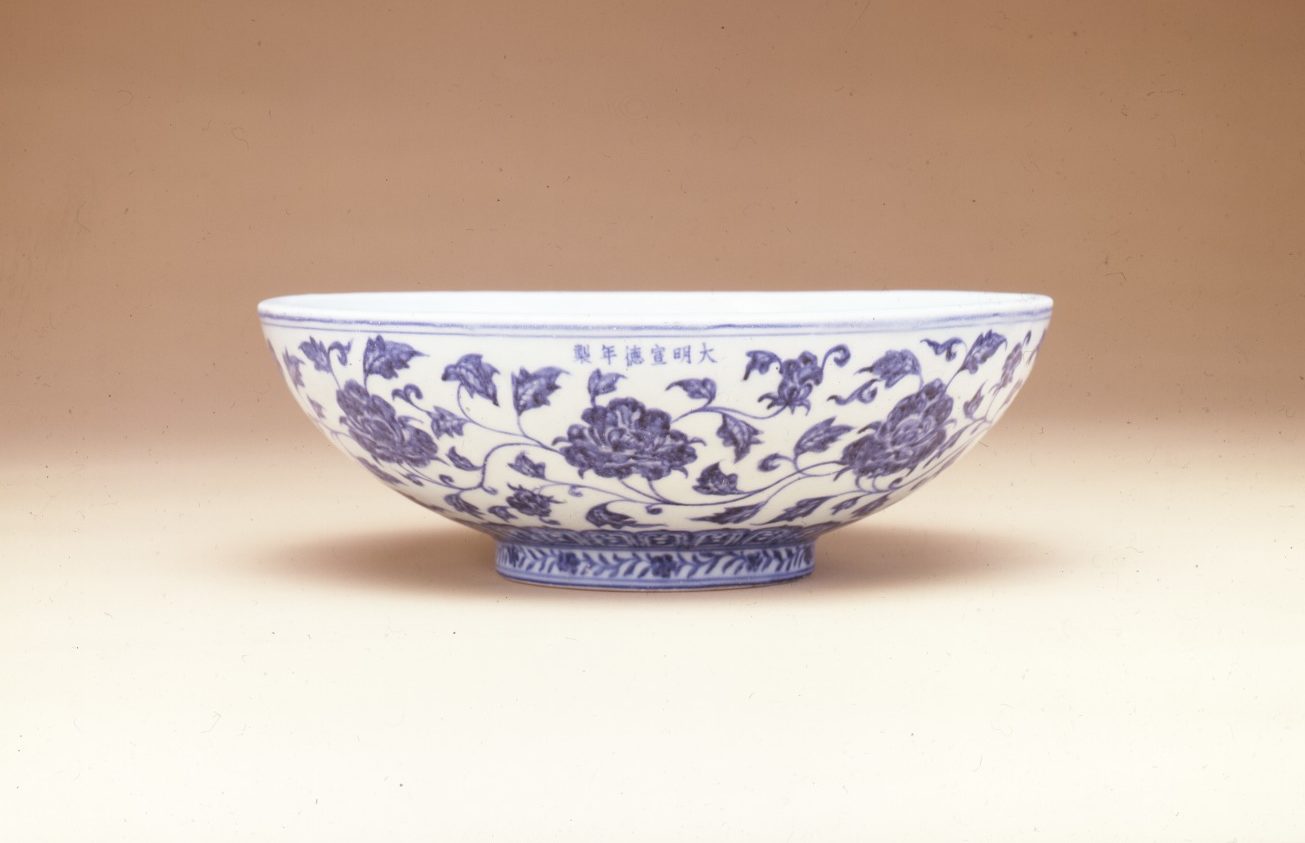

Colors of Sky and Clouds: Chinese Blue-and-White Porcelain

Through 10 outstanding works, this special installation traces the evolution of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain – from the 1st century, when Chinese potters began gradually perfecting a white, vitreous porcelain made from rich deposits of kaolin clay, into the 17th century, when foreign influences and new folk-art and popular motifs broadened the appeal of these works to merchant and scholar classes.

IMAGE CREDIT

Unknown, Dice Bowl or Fruit Offering Bowl, Ming dynasty, Xuande period, 1426-1435. Porcelain with blue underglazing. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Matthew L. Wong.

Mountains and Rivers, Flowers and Birds: Gifts from the Papp Family Collection

With hanging scrolls and fans, this special installation illuminates how classical Chinese ink paintings sought to reflect and show reverence to the beauty of the natural world through structured compositions of mountains, trees, rocks, and clouds, or birds, flowers, insects, and fruit, all suffused with a meditative rhythm.

IMAGE CREDIT

Jiang Tingxi, Peonies, Morning Glories, Cherries, and Chinese Cotton, late 17th-early 18th century. Ink and color on gold paper, mounted as fan on original staves inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Gift of Marilyn and Roy Papp in Honor of the Museum’s 50th Anniversary.

Clay and Bamboo: Japanese Ceramics and Flower Baskets

Clay and Bamboo presents examples of modern Ikebana ceramics and basketry that blend centuries of Japanese tradition with contemporary approaches to material and function. Simple and asymmetrical clay vessels contain slight, purposeful imperfections that enhance the innate qualities of the natural materials, while bamboo baskets showcase the techniques and symbolism of basket weaving.

IMAGE CREDIT

Hiroyuki Wakamoto, Tapered vessel with small mouth. Ceramic. Gift of Elaine and Sidney Cohen.

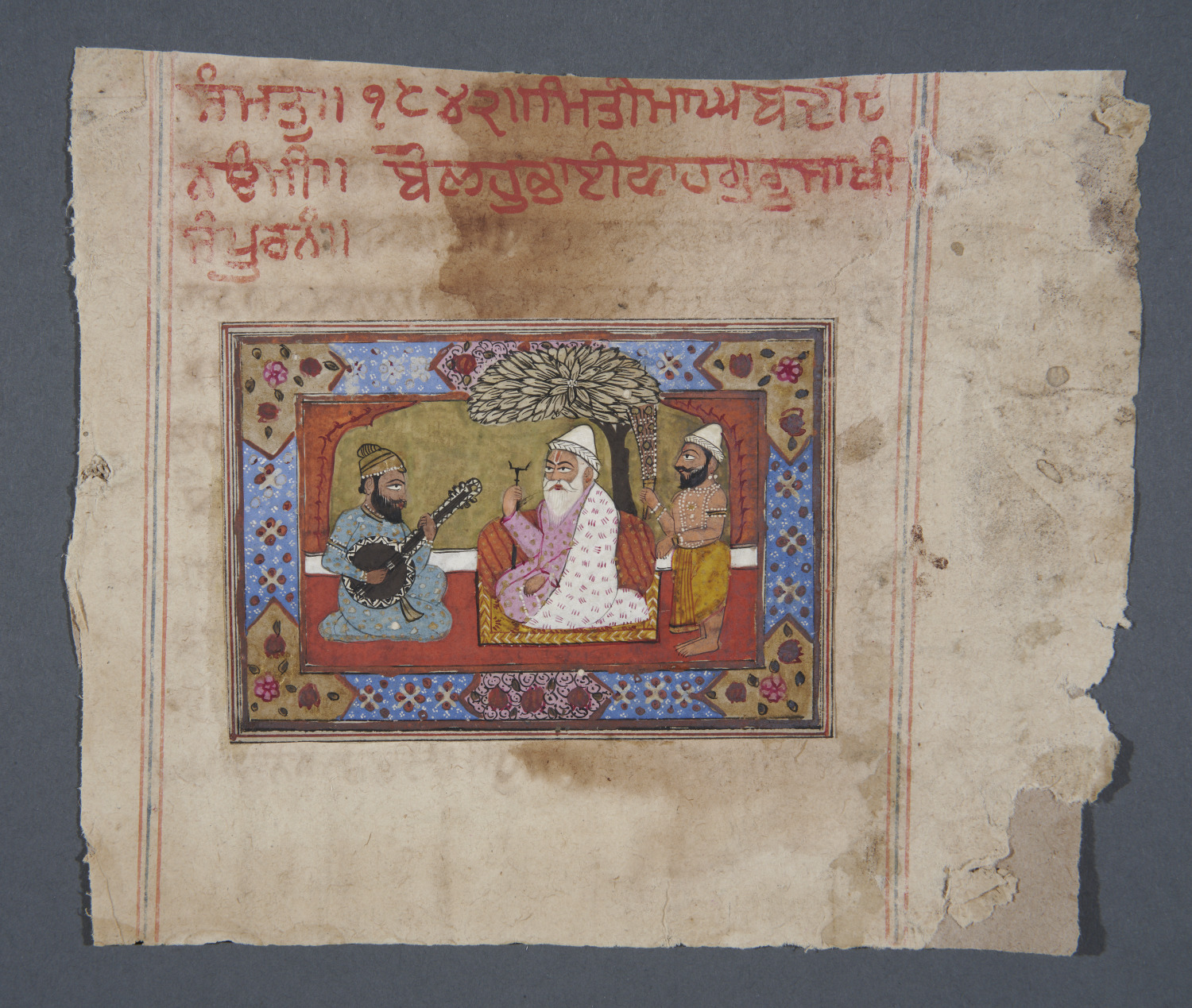

Guru Nanak: 550th Birth Anniversary of Sikhism’s Founder

Spanning four centuries, Guru Nanak showcases approximately 25 historical and contemporary works that depict stories of the Guru’s spiritual journeys and explore how his concept of oneness has informed Sikh writings and practices since the 15th century.

IMAGE CREDIT

Unknown, Guru Nanak and His Two Companions, not dated. Ink and color on paper. The Khanuja Family.

Emily Eden: Portraits of the Princes and Peoples of India

An English poet and novelist, The Honorable Emily Eden accompanied her brother, Lord Auckland, to India when he served as Governor-General, the colonial representative appointed by the British Empire, which occupied India beginning in the 19th century until 1947. Eden sketched and painted local life, ceremonial functions, and political events that occurred during Lord Auckland’s rule. Featuring Eden’s lithographs, this special installation offers an outsider’s perspective of the people of Northern India as they navigated a period of colonial rule.

IMAGE CREDIT

Emily Eden, Rajah Heera Singh (principal chief of the Punjab) (detail), 1844. Hand-painted chromolithograph on paper. The Khanuja Family.

Curating Seeking Immortality: Q&A with Janet Baker, PhD

Curious how Phoenix Art Museum staff installed the latest artworks featured in the Art of Asia Wing while social distancing? Janet Baker, PhD, the Museum’s curator of Asian art, and the Museum’s dedicated registrars and preparators used a floor plan with numbered rooms and walls, numbered art objects, and the video-conference platform Zoom. Check out a short montage video of Museum staff installing Seeking Immortality: Ancient Artifacts, along with a Q&A with Baker to learn more about her curatorial process.

A museum registrar is responsible for managing the care and organization of an art collection, including the logistics of moving artwork, documenting each art piece, and preparing artworks for display in exhibitions.

A museum preparator is responsible for installing and de-installing museum exhibitions, including completing the construction and deconstruction of gallery walls, hanging or arranging art objects, and placing exhibition graphic elements.

PhxArt: Tell us generally about the process of curating an exhibition. What comes first for you?

Janet Baker: Each curator approaches their process of selecting an exhibition topic and featured objects differently. In essence, there are two ways to approach the presentation of artworks. One is to combine similar types of objects so visitors can perceive the subtle and infinite variations between them. The other approach is to present different types of objects together and encourage visitors to consider what their connections or differences might be.

For me, I frequently spend time in the Asian art storage vault, simply looking at the objects in the Museum’s collection. I also visit the Art of Asia galleries often, so I am familiar with the space and how it can be utilized with both two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects. In my 20 years at the Museum, I have come to intimately know the strengths (and weaknesses) of the Asian art collection, knowledge that helps me determine the topics to explore through exhibitions.

PhxArt: Along with your deep knowledge of the collection, what other factors influence your work as you curate exhibitions and special installations?

Baker: I have spent quite a lot of time in Asia, which has permitted me to better understand the cultural framework that these objects come from. It also gave me opportunities to visit museums in these countries and perceive how they have been interpreted by their cultural descendants. I have lived in and traveled extensively through Asia, exchanged cultural ideas with scholars there, and seen the vast and varied geographical settings in which these objects were created. I incorporate the lessons I’ve learned into each exhibition, integrating objects in ways that allow visitors to understand the complexities of social and cultural evolution as well as the trading practices, migrations, religious faiths, military conquests, and cross-cultural influences that have come into play over more than 5,000 years.

PhxArt: What inspired Seeking Immortality: Ancient Artifacts?

Baker: Ancient cultural objects permit us to understand what people living in different times did, made, thought, believed, and experienced in their lives. They allow us to contemplate the questions that reflect our shared humanity. I often ask myself: How do these objects reflect or shed light on social roles, power, values, and the priorities of life and death? If an exhibition causes the viewer to think, feel, and ask questions, then I believe I have done my job well. I look forward to hearing our audiences’ responses to Seeking Immortality and their perceptions of these ancient societies.