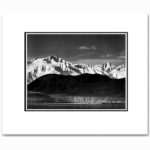

Long before Ansel Adams became one of the 20th century’s foremost American photographers, known for his iconic photographs of sweeping Western American landscapes and soaring, snow-covered mountaintops, he dreamed of becoming a classical pianist. Perhaps it was this foundational love of piano that inspired Adams to liken the photographic process to music. “The negative is the equivalent of the composer’s score,” he once said, “and the print is the performance.”

Ansel Adams: Performing the Print, on extended view in the Norton Gallery at Phoenix Art Museum, takes inspiration from Adams’ observation on the performative nature of print-making in photography. Featuring more than 60 photographs spanning the artist’s career and drawn from the Ansel Adams Archive housed at the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) in Tucson, the exhibition takes viewers on a journey through the evolution of Adams’ iterative process, from capturing the negative (the original “score”) to printing it to express a unique character or quality (the performance).

Fun fact: Ansel Adams co-founded the Center for Creative Photography in 1975 in collaboration with then-University of Arizona president John P. Schaefer.

Rebecca A. Senf, PhD, the chief curator at CCP who curated Performing the Print, pairs multiple prints of the same images throughout the exhibition, allowing viewers to see how Adams regularly explored various interpretations of his photographs. One pairing, for example, presents two noticeably different approaches to the portrait Spanish-American Youth, Chama Valley, New Mexico (ca. 1937). In one performance of the image, the subject is at a slight distance from the viewer, flooded in light as he rests his arms on a wooden fence, cumulonimbus clouds rolling in the sky behind him, his hat tilted to one side. In the second version of the portrait, the image is cropped, creating a more intimate feeling and viewing experience.

Ansel Adams, Spanish-American Youth, Chama Valley, New Mexico, ca. 1937. Gelatin silver print. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Ansel Adams Archive. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

“Adams mounted and signed both versions of these prints, which means he considered them both finished works. It’s not that one or the other was better or worse—they’re just different ways of seeing the same view.”

– Rebecca A. Senf, PhD, chief curator at the Center for Creative Photography

“Being able to show multiple versions of prints from the same negatives in this way helps the audience understand what Ansel Adams was doing,” said Senf. “You can tell someone about what Adams was thinking or what he was doing, but it’s ideal to be able to show them. To see, for instance, two prints from the same negative that are printed at different sizes, or to see how the dodging and burning caused one print to be darker or lighter, more subtle or more dramatic. Those are things you can see when you can compare the prints side by side.”

Photography 101: Dodging reduces exposure to lighten parts of the image, while burning increases exposure to darken areas of a photograph.

While the exhibition’s otherworldly moonrises and intimate depictions of homecoming and place reveal much about the interests and aesthetic of Ansel Adams the composer, it is the near imperceptibility of their differences—in angles, light, and shadows—that illuminate Ansel Adams the performer. More than a celebration of the legendary photographer’s work, Performing the Print underscores the work of the photographer’s hand and—regardless of maker—the painstaking efforts required to bring a creative vision to life.