Everything is a response to something.

In the 1950s, generations of Americans were in recovery. Survivors and witnesses of one of the deadliest conflicts in human history, they had faced the horrors of the Holocaust, murder at its most efficient extreme, only to awaken to the dawn of the Nuclear Age, a global race to perfect the most effective tool of mass destruction ever conceived.

As if to insulate themselves from the blood-soaked memories of humankind’s destructive power, many Americans, enriched by the post-War boom, fled the compact, communal living of urban centers to take up residency in sprawling suburban locales. After seeing for themselves the peril of being different, they entered a period of profound conformity driven by a desire to protect oneself from the dangerous proposition of individuality. Even unique geographic characteristics and cultural markers became blurred and homogenized, lost to the sanitized sameness of the mass-produced and a television culture that set the standard for well-heeled family life and suburban respectability.

It is from this post-War place that Abstract Expressionism was born, fueled by artists who had fled Nazi persecution. Led by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, the movement abandoned the boundaries of the literal and instead captured the gestural chaos of the period. Humanity, after all, had become unrecognizable; it made sense then that no common figurative language could capture the experience of life after so much sorrow, war, and lost hope.

But as Abstract Expressionism captured the collective imagination of artists and critics based in New York, other art groups with varying agendas bubbled to the surface across the country. In Chicago, a group of figurative painters called the Chicago Imagists created grotesque, surrealist work studying the human form, proudly divorcing themselves from all New York art trends. And on the West Coast, in San Francisco, something different emerged entirely.

It began with what is now known as the San Francisco Renaissance, a term that applies most specifically to the appearance of literary geniuses, including poets, writers, and philosophers like Allen Ginsburg, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Alan Watts, but which is now applied to all artistic expressions from the Bay Area during that time. As Watts aptly wrote in his autobiography, “…something else was on the way, in religion, in music, in ethics, and sexuality, in our attitudes to nature, and in our whole style of life.” And in the visual arts, the Bay Area Figurative Movement and Funk art were born.

Sweet Land of Funk, currently on view on the third floor of the Museum’s Katz Wing for Modern Art, explores the art movements of 1950s San Francisco. A survey of more than 20 works from the Museum’s modern and contemporary art collections by Funk and figurative Bay Area artists, including Viola Frey, Jay DeFeo, Bruce Nauman, Richard Diebenkorn, and Manuel Neri, the special installation creates a sense of the City by the Bay, Oakland, Berkeley, and beyond during the storied period of Beat poets and bohemians, of Haight and “Howl,” and of counter-culture that questioned conformity, ongoing military conflicts, the disparity of wealth, and other social issues that would fuel the revolution of the Baby Boomer generation.

Enrique Chagoya, An Object at the Limits of Language, 2000. Acrylic, oil, amate and linen. Gift of Friends of Mexican Art.

To begin simply, figuration came before the Funk. The Bay Area Figurative Movement emerged as a direct response to Abstract Expressionism and, for more than two decades, rebelled against the non-representational, with artists producing luminous portraits and vibrant landscapes, particularly those that represented their own geographical region. In Sweet Land of Funk, the movement is perhaps best represented through first-generation Bay Area Figurative artist Richard Diebenkorn’s Woman by a Window (1957), whose subject is a blank-faced figure rendered in a grey palette against the brightly lit backdrop of a sunlit, rural wasteland. The scene is reminiscent of a passenger waiting to board a flight in an airport built at the edge of the city it serves. A later example from the third generation of the movement is that of Manuel Neri, a student of Diebenkorn. His sculpture from his Arcos de Gesos series features two nude, chartreuse-painted, female figures knelt against a scuffed textural background. The forms appear poised yet uncertain, perpetually in a moment of decision—waiting to stand, to rise, or to rest.

Then came Funk art, from the depths of the San Francisco underground and influenced by the expansion of hippie counterculture and anti-establishment Beatnik aesthetics and expression. A response in its own right to the Abstract Expressionist movement, Funk Art became home to artists who embraced the lurid, the garish, the cartoonish, and the profane. While the sleek Minimalism of New York’s avant-garde became de rigueur on the East Coast, the Bay Area’s Funk embraced swirling psychedelia, and nothing was off limits—not sex, not gender, not anything to do with human identity.

In Sweet Land of Funk, the spirit of Funk art is perhaps best represented in Nude Man (1989) by ceramicist Viola Frey. The vulnerability of the seated nude male figure is obscured by the vibrant, kaleidoscopic colors that streak across his pink form in shades of blue, orange, and yellow. Despite the unnatural palette, which brings a lighthearted, almost comedic quality to the work, Frey’s figure is deeply human, his body fleshy and real.

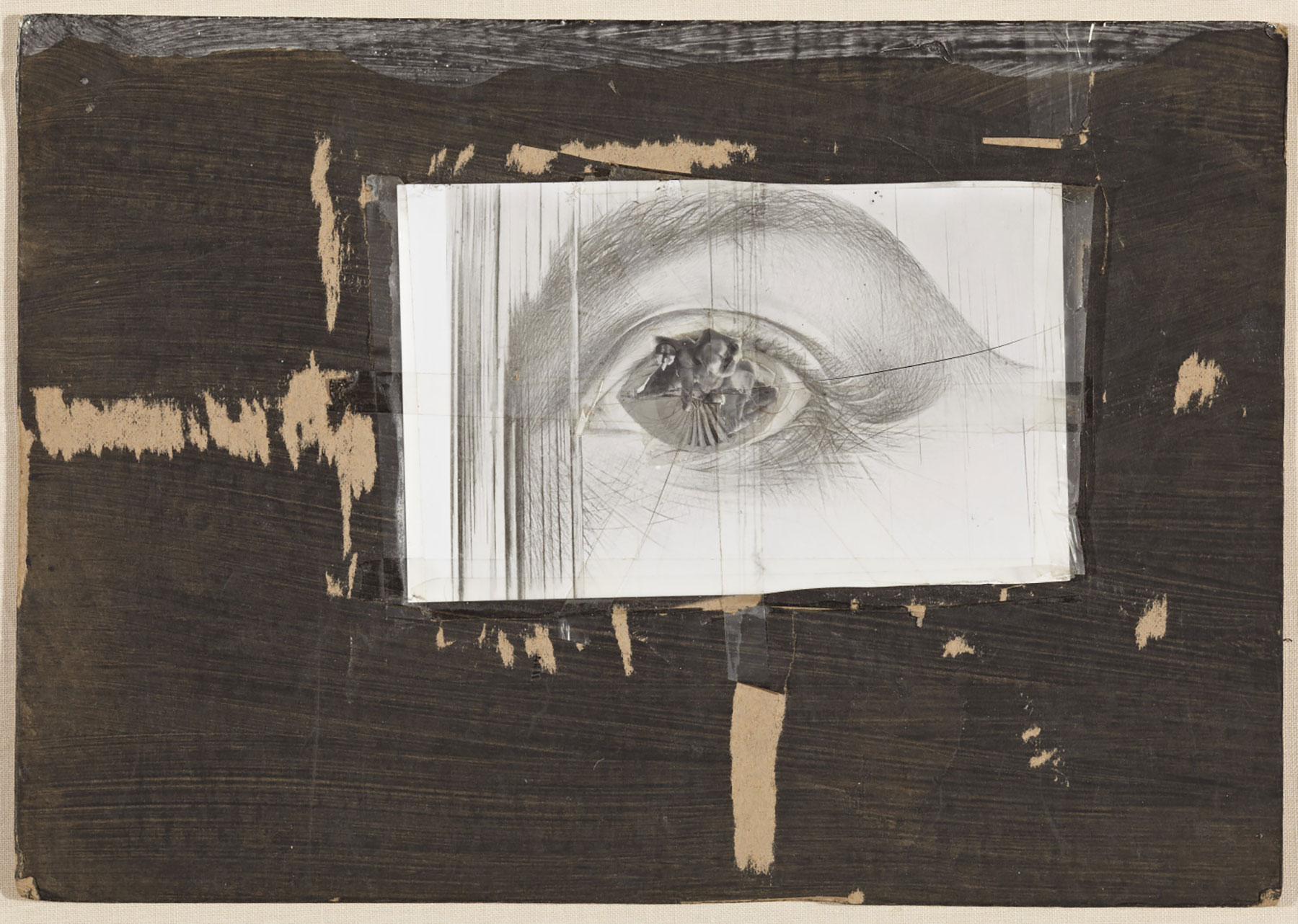

In contrast to Frey’s scultpure is Jay DeFeo’s Untitled (c. 1972-1973), a photo collage affixed with tape on a painted rag board. DeFeo, most known for her monumental work The Rose, which she completed over eight years, resisted identifying with any movement, though her work is emblematic of both Beat and Funk. In this work, DeFeo focuses on a single, exquisitely detailed human eye, framed by a pale eyebrow, with abstracted chaos emerging from the pupil.

Sweet Land of Funk moves through the extremes of northern West-coast artistic expression with deftness and ease, presenting a time capsule of the Bay Area before Big Tech, when San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkley were known not for sky-rocketing real-estate and crowded commutes, but for being weird, in the best possible way. It recreates the sense of a time before a Gap was built at the intersection of Haight and Ashbury, when a group of poets, artists, dreamers, and Beatniks crowded into a former auto-shop-turned-art-gallery in the city’s Fillmore District to hear Allen Ginsburg recite “Howl” for the first time. The art in Sweet Land of Funk was a response to Abstract Expressionism, yes, but it was also a response to the world that birthed it—a period of unrest and revolution. It is the work of a generation of artists who, born from war, answered destruction with creation, resisted erasure with vibrancy, to create radical expressions of peace, love, equality, and perhaps, best of all, hope.