Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana: In His Own Words

Sep, 08, 2020

ArtistsCommunityPhxArtist Spotlight

Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana: In His Own Words

CONTENT WARNING: Graphic content (extreme violence, sexual violence, self-harm)

The following blog post includes the candid and vulnerable stories of American veterans and their experiences on tour and with PTSD.

Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana is a father, husband, veteran, and photographer. Retired from the Navy, he has dedicated his art career to shedding light on the painful and enduring effects of PTSD on veterans and active-duty military personnel. His photographic and film project PTSD: The Invisible Scar has been featured in several publications, including The Recruiter Journal, AZ Foothills Magazine, Local Revibe Magazine, North Valley Magazine, Phoenix New Times, and ARTWISTA.COM, an online gallery based in Germany. He has exhibited his project and other work across the Valley at monOrchid, Public Image, Cartel Coffee Lab Phoenix, and Market Place One, and in Tucson at the Banner University Medicine Behavioral Health Clinic.

The stories of veterans featured throughout this post and in each image’s caption are painful and may be difficult to read, but they are important.

Here’s Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana, in his own words, sharing his personal journey and those of his fellow veterans.

“As a retired Navy veteran and photographer, I am able to bridge the gap between the worlds of artist and veteran to expose invisible scars that these brave men and women bare.”

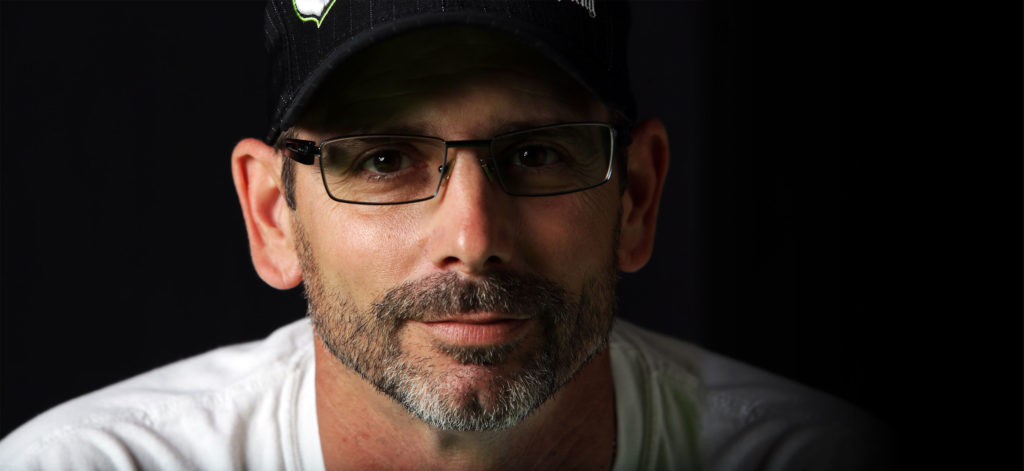

Boats, 2015. Photo by Wayne Rainey.

PhxArt: Where are you from, and when did you first become interested in photography?

Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana: I hail from Connecticut originally and moved to Vermont as a youngster. After I graduated from high school, I joined the U.S. Navy back in 1984. I started to take some photos here and there with a Pentax K-1000 but was never able to truly pursue my passion because of my time in the service.

PhxArt: What inspired you to finally become a professional photographer, and what motivates you to continue creating?

Oshana: After I retired from the Navy in 2004, I picked up the camera again, and it was a photo of one of my twin daughters that inspired me to try out photography. I was taking photos of them for my parents for Christmas. They were 2 and ½ years old at the time and were getting upset, so I told them to do what they wanted and one of them started to play with a Christmas ornament on the tree. I took the shot, and it looked like it should have been in the Saturday Evening Post. That reignited my passion and thought that I should pursue photography as a profession.

Some of my many inspirations and motivations to keep creating are my brothers and sisters in arms, my family, and Native American rock art. I also feel privileged to get out of bed every morning and see the beautiful sunrises and sunsets of Arizona.

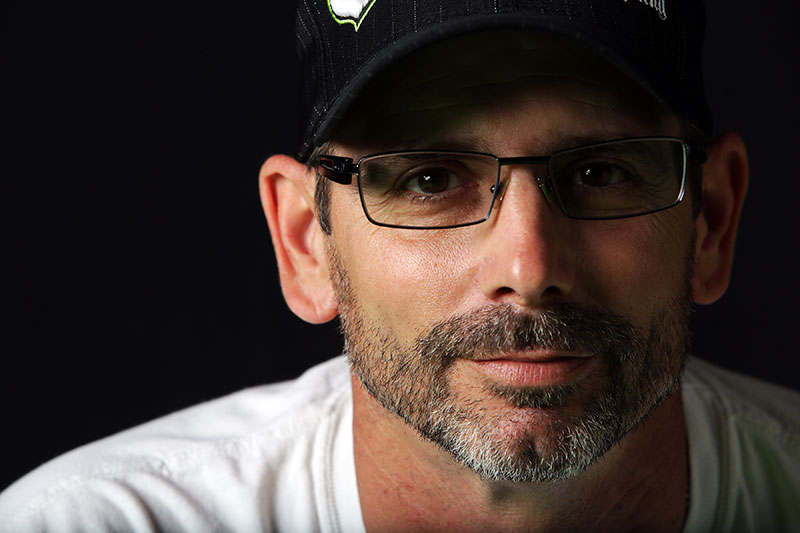

Brad, US Marines. Brad is my nephew-in-law and is married with three children. He has been deployed to Iraq and/or Afghanistan three times. He has lost eight of his fellow Marines to suicide as a result of PTSD. I was told by my niece (his wife) that I needed to talk to him and try to get him to sit with me. After the fifth death of a friend, he reached out. We sat in the studio for about an hour and a half talking while I photographed him. The feeling was so overwhelming for me that I had to take a break from the session. Brad had started to get help but also started using alcohol to the point that he almost lost his family. Since we sat together, I have started to videotape my sessions. His was the first one I filmed, and during his session, he told me he had contemplated suicide. He has since sought more help, and it has done wonders for him. Image credit: Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana, Brad, 2013. Archival Print. Courtesy of the artist.

PhxArt: Tell us about your veteran series. What inspired you to do this work, and what do you seek to explore through it?

Oshana: PTSD: The Invisible Scar is a photographic and film documentary project about veterans who have been diagnosed with PTSD. It invites viewers to look beyond the façades and inside the private lives of a few of our country’s veterans who suffer from the disorder.

The inspiration for the project came after I was awarded a grant from Wayne Rainey at monOrchid to work on a project called For The Good. At the time, I was a photographer without a “home” (i.e., studio) to call my own, and as with many beginner photographers, I was photographing the historical buildings in the city proper of Phoenix. After Wayne awarded me the grant, we started to chitchat, and I had told him that I was a member of the VFW Post 1433 and the VFW Riders White Tank Chapter. He suggested photographing wounded warriors. I thought for a little bit, and it came to me that no one knows what PTSD looks like because often there aren’t any visible scars or trauma like missing limbs and such. I needed to put a face to it.

As a retired Navy veteran and photographer, I am able to bridge the gap between the worlds of artist and veteran to expose these invisible scars that these brave men and women bare. The purpose of this project is to show the public that there are scars from combat other than the visible ones. I also want viewers to learn that even though these veterans have come back in one piece physically, they are still fighting the memories of war and their comrades. I have been extremely honored and humbled by the men and women who have participated by sharing their stories and allowing me to photograph them in a vulnerable place.

Danee, US Army National Guard. Married with three children, Danee completed two tours in Iraq. While on her second deployment, she was raped by a fellow soldier. We may think we are safe in our own camp, but there are enemies who lurk around us no matter where we are and no matter the situation. Danee’s relationship with her family is now so strained that when she arrived to our photo session, she was already in tears. Image credit: Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana, Danee, 2013. Archival Print. Courtesy of the artist.

PhxArt: How many veterans have you photographed so far? How do you find participants and get them to open up to you?

Oshana: At this point I have photographed 24 people and filmed seven others. I’ve used Facebook, Craigslist, Twitter, word of mouth, and the list goes on. Before I even pulled out my camera the first time, I had to somehow get the veterans to sit with me and open up about something so extremely personal, which is still a challenge. My very first sitting was the most difficult because of those fears. Daniel answered my Craigslist ad, and we sat in the living room at the studio and started talking to figure out if he was going to be able to sit for the portraits. About 20 minutes into our visit, I started to notice he was getting a little fidgety. I asked if he was ok, and he answered, “I will be alright in a few minutes. I feel like someone is coming at me with a fixed bayonet trying to kill me.” I thought, “This is the end. Do I need to call 9-1-1? Do I need to have someone here?” I was nervous. A few minutes later, he said that he was better and we could keep going with the interview. I learned that most of these men and women know when they are about to have or are having a flashback, a panic attack, or an anxiety attack, and they know how to settle it down and re-ground themselves by breathing, getting out into the fresh air, or through a multitude of other techniques. Some of the bad coping measures are alcohol and drug use, social isolation (which has been difficult for many during these trying times of COVID-19), and running away. I also had to learn how to raise money for the initial printing and mounting of the photos, which was one of the most difficult things to do when you have a family and a job, you’re going to school, and you’re trying to be a professional photographer.

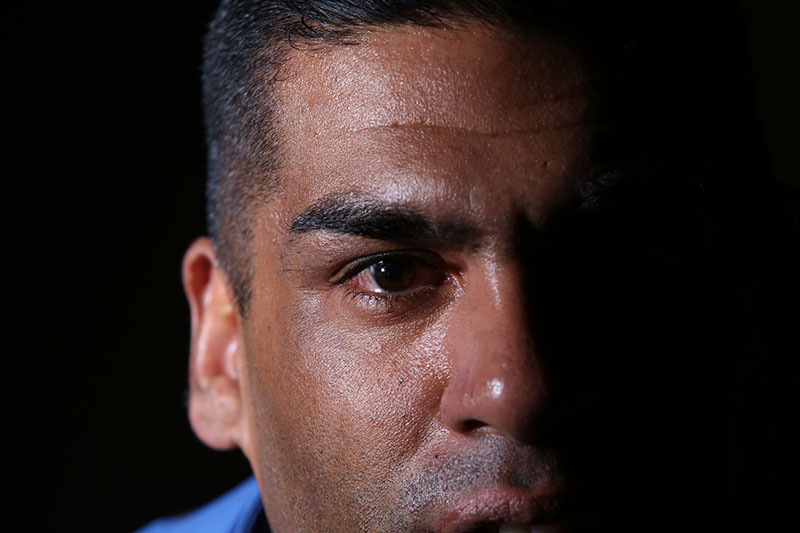

Ricardo, US Army. Ricardo lost his life partner and two other friends to PTSD-induced suicide. With the most recent friend, Ricardo knew something was wrong, so he called and called to no avail. He decided to go to his friend’s apartment and found a blood trail from the apartment to where his friend’s car was parked. Ricardo called the police and then went looking himself. The following day, he found his friend, dead in the car. Image credit: Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana, Ricardo, 2016. Archival Print. Courtesy of the artist.

PhxArt: How is your project working with veterans different from others you’ve seen before?

Oshana: I have seen projects that put a number on each photo as if they were trying to keep track or something. I do not want the participants to think that they are a number, a subject, or anything like that. It is bad enough that some entities like the VA, the military, and others have put that number on them. These men and women have put their lives on hold to serve our great country—they have “been there, done that.” The pride that these men and women exude is contagious, the sadness and turmoil they contend with is overwhelming, and the nightmares of the past are haunting. Most of them have put on such a façade that most actors would have to say they’ve given Academy-Award worthy performances. I have actually served side by side with some of these men and women, and I had no clue they were in such pain. They have opened up their hearts and minds and placed their trust in me to tell their stories.

By allowing these individuals to open up about their struggles, as the artist, I have been able to capture incredibly emotionally charged moments. Sitting for their sessions has helped some to start the healing process. As I interview each veteran extensively and learn their stories, I capture a pure image that relates to the sacrifice and suffering they endure and I’m asking the viewer to take a moment to try and understand what these veterans have gone through.

Ace, US Army. An Army Recruiting First Sergeant, Ace has completed four tours in Iraq and Afghanistan as an explosives dog-handler. One day, his unit left for a patrol at 0530. They were to clear IEDs on a road so littered with them that by 1000 hours, they had gone less than a mile. The Infantry Unit Lieutenant decided to dismount from the vehicles and go through a farm field to start clearing. Ace started his grid search with his dog, but the dog experienced a change in behavior. The dog smelled explosives in the area, but they had to stay on grid. Once at the line, Ace completed a 180-degree turn and started up the opposite direction searching. About five minutes later, there was an explosion behind him, and eight soldiers were lost. Ace did not know why those soldiers were in that area because he had not cleared it yet. Was it an error by the Lieutenant? Was it because he had not pushed the Lieutenant to go over to that area when the dog’s behavior changed? These are the questions Ace thinks about when he remembers that day. Image credit: Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana, Ace, 2017. Archival Print. Courtesy of the artist.

PhxArt: What have you learned from this project?

Oshana: Most people have heard the horror stories about PTSD, that these people are crazy—they snap at a moment’s notice, including myself. I have learned that some of the contributing factors are combat, sexual assault, and life-threatening experiences. I’ve also learned PTSD is not confined to the military— civilians can also be subject to this diagnosis.

PhxArt: Who are your greatest artistic influences?

Oshana: There are a lot of people who influence me as an artist. The first is Wayne Rainey, for having the courage and trust in me to allow me to use his studio to its fullest potential. Some others are Michael Meyers, a computer graphics artist; Doug Milles, a muralist and activist; Jon Linton, a photographer and activist; Antoinette Cauley, a painter; Brian Boner, a painter; Nicole Royce, an artist, curator, and gallerist; and Bryan Kinkade, a photographer. These are just a few of the artists who have touched me in one way or another through their ambition to do something meaningful, their confidence, their choice of color, the lighting they use to create emotion in a photograph, but mostly through the encouragement they have given me over the past seven years.

Chris, US Army. A former combat medic, Chris completed two deployments with the same unit and friends. One day, he went out on patrol with his best buddy, and about halfway through, as they walked in two columns on either side of a road, his friend stepped on a landmine. The concussion from the explosion blew the patrol in all directions and put Chris on his back with ringing in his ears. In pain, he tried to help his friend, who was bleeding badly, but there was no way to save his friend’s life. Chris wore the same boots he was wearing that fateful day to our photo session. About three months after the session, I finally worked up the courage to ask him what he did with the uniform he was wearing that day. He told me he had put it in a safety deposit box in New York. Image credit: Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana, Chris (Doc), 2013. Archival Print. Courtesy of the artist.

PhxArt: What can our community expect to see next from you?

Oshana: I am currently working on a couple of projects that are very close to my heart. I have been photographing examples of Native American rock art, which are some of the oldest and most fragile treasures of Arizona. I’ve photographed areas that are accessible by hiking, whether it’s a short hike out at South Mountain, or a six- to eight-mile trek to Indian Springs in the Eagle Tail Mountain Wilderness. I’ve additionally photographed some rock art driving up to Perry Mesa to the Agua Fria National Monument.

I am also working with PJ Gal-Szabo on a documentary that is now in the editing phase called The Invisible Scar. I invited four veterans to participate in a non-clinical, non-sterile, and open environment to talk in a group setting about their trials and tribulations with PTSD. It was so amazing to witness their free flow of thoughts without them feeling the need to look over their shoulders to see if they were saying the right thing.

See more

To discover more work by Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana, visit his website; follow him on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Vimeo; and check out the following resources to learn more about his current project and upcoming documentary.

PTSD: The Invisible Scar Facebook page

The Invisible Scar Facebook page

The Invisible Scar

#CreativeQuarantine

We’re curious how creatives are navigating the time of coronavirus. Christopher S. “Boats” Oshana shares what’s giving him life as a creative during quarantine.

Oshana: The thing that gives me the most life is being able to share everyday with my family. This past January, my wife was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer after being breast-cancer free for 15 years. She has been such a rock in my life—she keeps me busy. With my wife having a compromised immune system with the cancer, it has been hard to photograph veterans, with the possibility of contracting the virus. So one of the biggest things that I have been doing during this time of COVID-19 and social distancing is research for my projects. I have also been reading an excellent book by Judy Weiser called Phototherapy Techniques: Exploring the Secrets of Personal Snapshots and Family Albums. It is fascinating to learn how photos have been introduced into counseling sessions and how similar it is to what I am trying to accomplish with each of the veterans who I have photographed. I have also been doing some wood-working projects, making rustic American flags, challenge coin racks, and a set of cornhole boards in the garage.

Categories

What can we help you find?

Need further assistance?

Please call Visitor Services at 602.257.1880 or email