Let There Be Light

Apr, 25, 2020

Art

Let There Be Light

From the scientific to the metaphorical, light is inextricably linked to the human experience. In many religious traditions, it is the first act of creation. In science, light particles, moving rapidly through our universe, contain all colors of the spectrum. In metaphorical language, it can symbolize knowledge, wisdom, hope, and ascension to a higher plane of consciousness, transforming us from the terrestrial to the divine. And sometimes, it’s just…light. But oh, the things we can see when we remember to turn on the light.

Explore these sculptures and installations in the Museum’s collection that illuminate our galleries and spaces and spark new ideas about the convergence of art and technology.

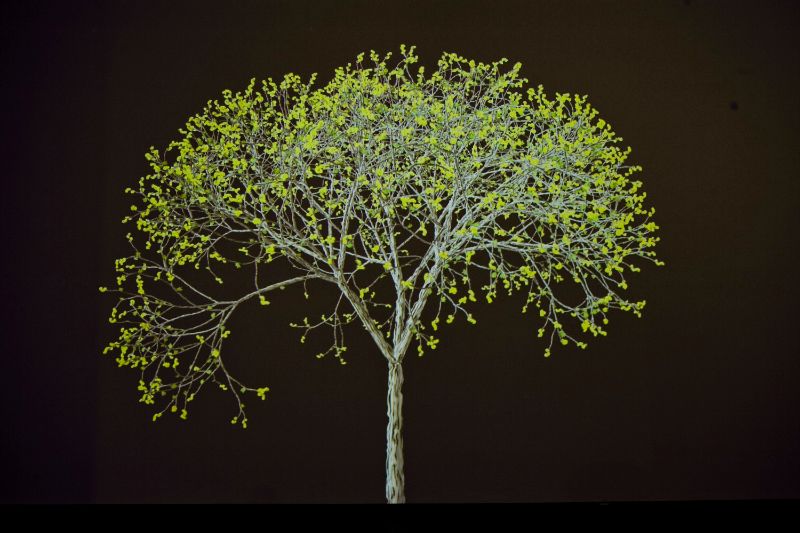

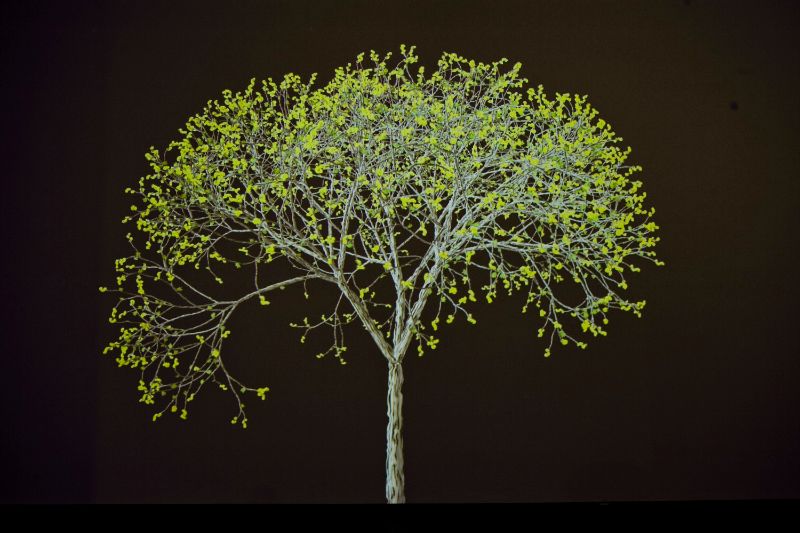

Mike Kelley 13 (2008) by Jennifer Steinkamp

Jennifer Steinkamp has been a pioneer in digital animation since the early 1990s, working with projected digital media to explore architecture, space, motion, and perception. This work by the American artist was digitally constructed on a computer without the use of existing images and represents a wind-blown tree changing with the seasons. Constantly moving, it has no beginning nor end and mimics the relentless shifts of both nature and technology.

LEARN MORE

Yayoi Kusama, You Who are Getting Obliterated in the Dancing Swarm of Fireflies (Tú que estás siendo obliterado por una multitud de luciérnagas danzantes), 2005. Mixed media installation with LED lights. Museum purchase with funds provided by Jan and Howard Hendler.

You Who are Getting Obliterated in the Dancing Swarm of Fireflies (2005) by Yayoi Kusama

Perhaps the single most iconic and popular work in the Museum’s collection, this installation, colloquially referred to as Fireflies, is an example of one of the acclaimed infinity mirror rooms by the Japanese artist, examples of which exist at museums all over the world. Born in Japan in 1929, Yayoi Kusama drew inspiration for her work from hallucinations she began to experience when she was a child, in which lights and spots invaded her field of vision. In many ways, her infinity mirror rooms duplicate the experience of those visual phenomena. Fireflies, which can only truly be experienced in person, is filled with pinpoints of light that slowly shift colors, creating the illusion of moving through stars in a boundless universe. But how did Kusama do it? In reality, the immersive, seemingly infinite installation is a rectangular, 25-square-foot room with mirrored walls, a Plexiglass ceiling, and a polished black-granite floor. And that endless array of stars or fireflies? Just the reflection of 250 suspended LED lights.

LEARN MORE

The Last Scattering Surface (2006) by Josiah McElheny

Designed for the Museum’s expansive Greenbaum Lobby, this iconic glass sculpture, often described as a chandelier or a glass snowflake, is typically one of the first artworks visitors encounter. Part of the American artist’s Big Bang Series, it attempts to explain the creation of the universe, its bright center emitting radiant extensions that allude to the theory that the universe emerged rapidly from an extremely dense state more than 14 billion years ago. The sculpture’s title is drawn from a scientific term describing the moment the universe transitioned from densely opaque to transparent, when light particles separated from matter and began to travel freely through space. The object’s design is based on a 1965 chandelier commission for the Metropolitan Opera House in New York.

LEARN MORE

Glenn Ligon, Palindrome #1 (Palíndromo No. 1), 2007. Neon. Museum purchase with funds provided by Contemporary Forum, Adam and Iris Singer, and anonymous donor.

Palindrome #1 (2007) by Glenn Ligon

One of the Museum’s most well-known “selfie” opportunities, this iconic neon sculpture by Glenn Ligon is often referred to by the piece’s phrase: “Face Me I Face You.” In truth, the title of the piece is Palindrome #1, though writers and grammarians alike will often be the first to say the phrase isn’t actually a true palindrome. When it comes to words, we suppose they’re right—except Ligon intended to create a conceptual palindrome, not a verbal one. Here he extends beyond the grammatical. His words “Face Me I Face You” refer to the concept wherein, in any given relationship, the “me” and “you” could refer alternatively to either one of two parties in an exchange. This work is a strong example from Ligon’s body of work, which explores issues surrounding race, language, desire, and identity.

LEARN MORE

Categories

What can we help you find?

Need further assistance?

Please call Visitor Services at 602.257.1880 or email