Pia Camil, Espectacular telón, 2013. Hand dyed and stitched canvas. Gift of Nicholas Pardon. Image courtesy Nicholas Pardon.

Espectacular telón by Pia Camil (Mexico)

Made of hand-dyed and stitched canvas, Espectacular telón (2013) is an abstract interpretation of the used, recycled, and abandoned billboards that line Mexican cities and highways. Effectively a three-dimensional painting without the need for paint, the work is indicative of Camil’s continued interest in highlighting the ruinous impact of commercialism on the urban landscape.

Sergio Vega, Shanty Nucleus After Derrida 2, 2011-2013. Installation, Inkjet vinyl prints mounted on syntra. Gift of Nicholas Pardon. Image courtesy of Nicholas Pardon.

Shanty Nucleus After Derrida 2 by Sergio Vega (Argentina)

Inspired by Derrida’s theory of deconstruction, Shanty Nucleus After Derrida 2 (2011-2013) presents yellow monochrome planes suspended in space, creating an array of configurations and walkways that enable an interactive viewing experience. These various planes constitute the color ground on which photographs of “shanty” homes have been mounted to create fragmented sculptural formations.

Critical Theory 101: Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) was the founder of the theory of deconstruction, a way of criticizing literary and philosophical texts as well as political institutions. A rejection of structuralism, which holds that words and artifacts have inherent meanings that must be discovered through analysis, deconstruction asserts there is no one-to-one equivalence between word and meaning. Instead, words hold traces of many meanings within them. By its nature, deconstruction therefore rejects the idea of predetermined and inalienable binaries, the reduction of meaning to set definitions, and the possibility of an absolute truth that makes sense of our place and purpose in the world.

Louise Nevelson, Royal Tide V, 1960. Painted wood construction. Museum Purchase with funds provided by Contemporary Forum. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Royal Tide V by Louise Nevelson (United States)

Nevelson’s imposing wood sculptures are commonly referenced in relation to artistic tropes such as Abstract Expressionism and assemblage. Usually constructed in monotone colors like black, white, and gold, her assemblages also bear a strong resemblance, albeit in three-dimensional space, to the work of Joaquín Torres-García and his School of the South. In Royal Tide V (1960), Nevelson uses discarded pieces of wood to construct abstract compositions framed within gridded structures.

Torres-García advocated a theory of art called Constructive Universalism, featuring pictographs set within grids.

Carlos Mérida, Juego de líneas (Line Game), 1964. Watercolor. Gift of Mr. Edward Jacobson. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Juego de líneas (Line Game) by Carlos Mérida (Guatemala)

Known for his paintings that fuse Pre-Columbian aesthetics with pictorial ideas culled from Cubism and Surrealism, Carlos Mérida spent extended periods of time in Europe. He uses elements of Mayan glyphs in relation to European aesthetic trends and motifs of the time to forge a stronger relevance to his heritage. Juego de líneas (Line Game) (1964) features his singular geometric shapes.

From 1910 to 1914, Mérida lived in Paris, where he became acquainted with artists like Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani, who ultimately helped shape his artistic confidence using new forms.

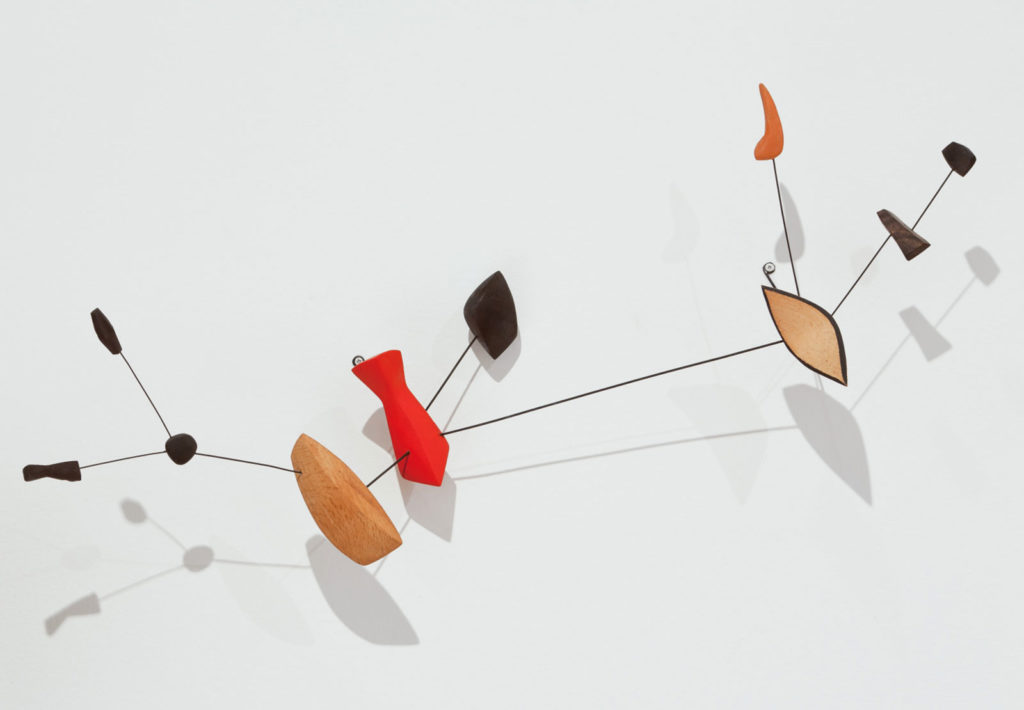

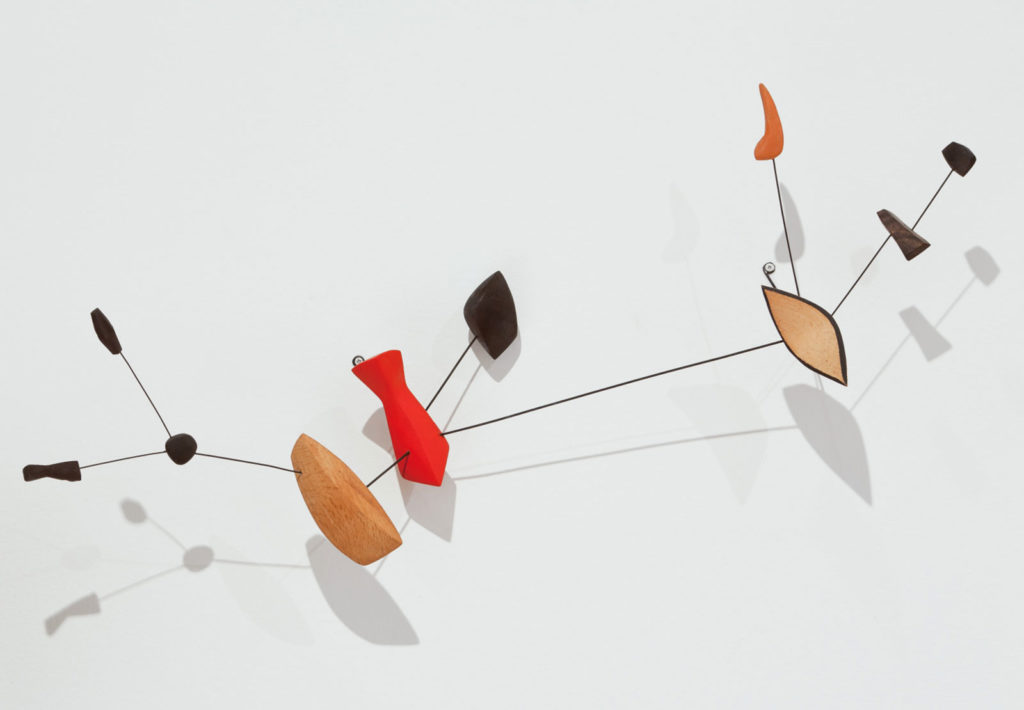

Alexander Calder, Constellation with Orange Anvil, 1960. Wood, steel wire, and paint. Bequest of the Estate of Orme Lewis. © 2020 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Constellation with Orange Anvil by Alexander Calder (United States)

Alexander Calder’s Constellations series demonstrates the artist’s deep interest in poetic systems. Works such as Constellation with Orange Anvil (1960), which is rendered in painted wood and wire, evokes the movements and forms of energetic forces in a fixed yet vibratory state. “I was interested in the extremely delicate, open composition,” Calder maintained of these works. Named by James Johnson Sweeney and Marcel Duchamp, the Constellations also embody biomorphic forms that bring to mind works by Calder’s contemporaries Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy, and Jean Arp. The series gave Calder yet another creative outlet, beyond his iconic mobiles and stabiles, to investigate primary shapes and colors through dynamic, abstract compositions on a relatively small scale.

Liz Cohen, Him #1, 2015. Pigment print. Courtesy of the artist.

Untitled (Him [for Eric/a]) by Liz Cohen (United States)

American artist Liz Cohen is based in Phoenix. In Untitled (Him [for Eric/a]) (2015-2016) the wool and silk from weavings by Loja Saarinen meet the walnut from an Eames chair, an example of mid-century modern furniture. The work marries abstraction with image making and the artist’s interest in representing the difficulties of radical self-expression.

In the late 1920s, Finnish-American textile artist and sculptor Loja Saarinen operated Studio Loja Saarinen and served as head of the department of Weaving and Textile Design at Michigan’s Cranbook Academy of Art, where Cohen created Untitled (Him [for Eric/a]).